I liked this editorial from the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

By: Ben Clarsen, Hilde Moseby Berge

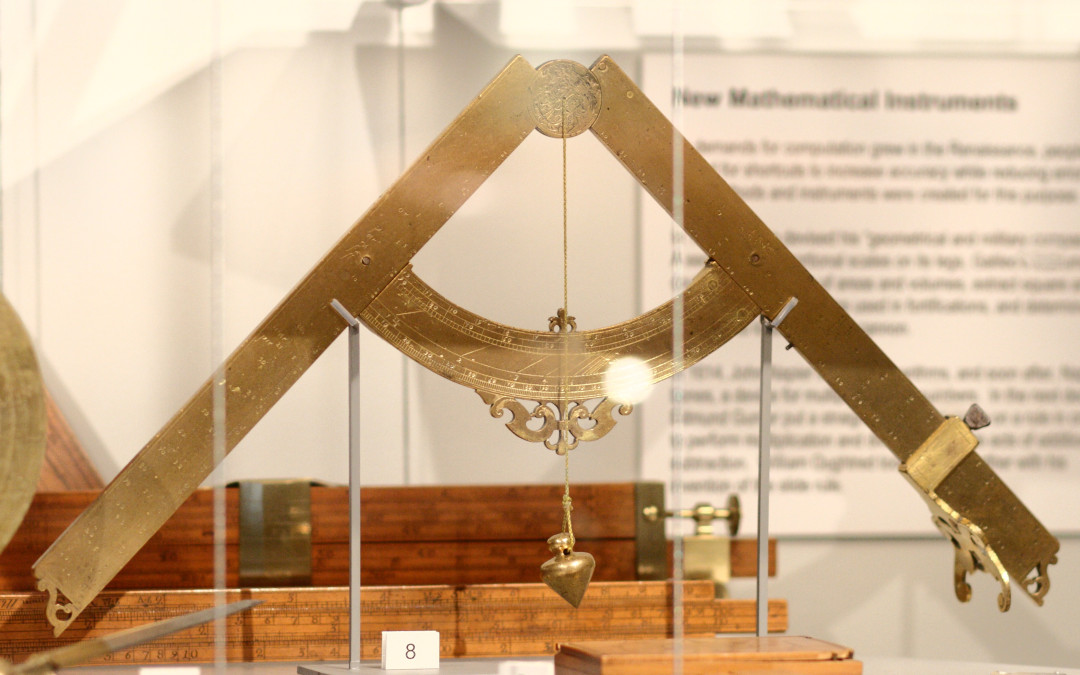

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) is often referred to as the father of modern science. Initially a medical student, his obsession with measurement soon turned him to physics, mathematics and astronomy. Galileo was the first to accurately measure time by harnessing the principles of the pendulum and his improvements of the telescope led to massive advances in the fields of physics and astronomy. In particular, he provided the first empirical evidence that the earth revolved around the sun, and not vice versa. The 17th century’s ‘Steve Jobs’ figure, Galileo invented the microscope, thermometer and compass. Just as Jobs revolutionised our thinking towards mobile computing by promising ‘a thousand songs in your pocket’, Galileo rocked his world by saying ‘measure all that is measurable, and make measurable what is not.’

Is our digital revolution going be considered another ‘golden age’? For sports clinicians and scientists, technological advances are opening up possibilities we could previously only dream of, particularly when it comes to measuring what was previously immeasurable. Our brilliant issue cover depicts new measurement possibilities in sports medicine. This picture illustrates how Gilgien et al turned the world’s best ski slopes into biomechanics laboratories by harnessing satellite positioning and digital terrain modelling technology. As discussed by Bere and Bahr, linking this innovative approach to existing injury surveillance may be an important step towards prevention of skiing injuries. Simulation of reallife game situations in the laboratory is another creative biomechanical approach featured in this edition, with Kristianslund et al making detailed calculations of side-step cutting in handball.

Nowadays it is not just songs in your pocket, but a virtual sports medicine clinic and performance lab in there too. Smartphones are powerful tools for collecting and communicating information, and according to Verhagen et al, electronic-health (eHealth) is the future of sports medicine. A good example of this is provided by Grindem et al, who show how online reporting of sports participation can be used to track patients’ return to sport after an anterior cruciate ligament injury. Similarly, Clarsen et al describe how an Internet questionnaire can help to optimise the health of Norway’s Olympic athletes. Both these papers describe methods that would have been logistically impossible prior to the digital revolution. The same might be said about the study by Bjørneboe et al, who use video analysis to make important recommendations about injury prevention in football.

Also in sports cardiology, computer measurements of ECG are taking over from the traditional ‘ruler-on-paper’ approach. However, as Berge et al demonstrate, the prevalence of abnormal ECG findings in athletes differs significantly depending on the measurement methods used.

New measurement technology will probably fascinate some and irritate others. We are sure though, that as new methods prove their scientific and practical value, they will be appreciated by the sports medicine world. Galileo, on the other hand, met so much resistance to his indications that the earth revolved around the sun that he was sentenced to life imprisonment and died after 9 years in house arrest. Today his revolutionary measurements are accepted as fact.

Reprinted From: Clarsen B, et al. Br J Sports Med May 2014 Vol 48 No 9