This article focuses on an athlete’s function after injury; much of it was written and researched by one of my students, Tina Schumacher. Thank you Tina for all the work you put into this!

So, after an injury or surgery, you complete the required rehab and all should be good.

- After rehab for Achilles tendon injury, running should be fine, right?

- After ACL reconstruction, playing soccer again is easy, right?

- How about after shoulder surgery? Swimming’s a piece of cake . . . or isn’t it?

At first glance, it would seem that as long as the physical components (like strength and flexibility) of an injury/surgery are addressed, there really should be no issue returning to the sport or activity or job we love. Well, there is much more to it than that as recent research has shown us.

When designing a rehabilitation program, a variety of factors should be considered. Although the physical components are an obviously important aspect of physical therapy, other, non-physical components–such as an athlete’s emotional and cognitive response to the injury–should be factored into the rehab process as well. Pain and fear of movement are becoming more popular research topics. While much of the research in this area has focused on persons with low back pain or carriers of the sickle cell trait, there is a growing body of research in other areas, like reconstruction after the dreaded tear of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL).

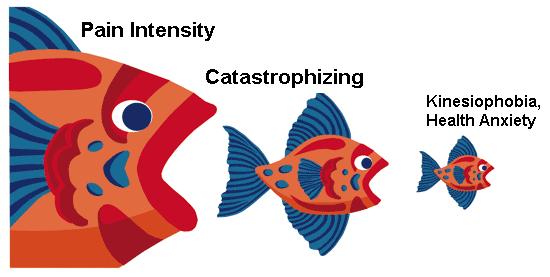

By definition, kinesiophobia is the fear of movement. Although the meaning of the word may be straight forward, the diagnosis and measurement of this psychosocial response to injury is not entirely understood. Early fear-avoidance models suggested that the avoidance was not directly related to actual pain, but instead was based off of more environmental factors associating pain to fear (Turk & Wilson, 2010). More contemporary models have expanded on these earlier models and commonly exhibit the following characteristics:

- After an injury, a person will determine the extent to which the perceived pain is harmful. They may misinterpret their body’s reaction to pain (e.g., pain catastrophizing).

- Pain may result in a negative interpretation and may cause a physiological, biological, and cognitive fear response.

- This shift in thinking results in an overall avoidance of the activity, and other everyday activities, because they are thought to be harmful.

Keeping this model in mind, fear avoidant behavior has the potential to be detrimental to rehabilitation of musculoskeletal injuries. Over sensitivity to a stimulus and disuse are often associated with pain, which can lead to long-term problems (Picavet et al, 2002). Further, if this association of fear is not detected early enough, physical therapy and other medical help will not have a significant effect on the pain (Gordon et. al., 2004). Determining pain in an earlier stage of the rehabilitation can help lessen the effects of associations of fear. As mentioned above, much of the research so far has pertained to lower back problems (Picavet et al, 2002 & van der Hulst et al, 2010). These findings have shown that kinesiophobia is common and needs to be addressed in order to reduce the risk for chronic pain problems. Recently, studies have looked at kinesiophobia on ACL reconstruction surgery (Chmielewski et al, 2008).

The University of Florida’s Therese Chmielewski has been at the forefront of research for fear avoidance following ACL reconstruction. In a recent article, she and her co-authors conclude that, “interventions aimed at increasing self-efficacy for rehabilitation tasks or decreasing fear of movement or reinjury have the potential to improve short-term outcomes for knee pain and function.” So, should you have your ACL reconstructed, shoulder scoped or Achilles tendon rehabbed, please be sure that your physical therapist has included activities to improve your comfort and confidence when participating in your sport or activity of choice.

As silly as it sounds, pain is not always bad, it usually tells us when something is wrong, and it’s good to know when something is wrong. When we begin to focus on that pain, injuries become debilitating and limit our abilities to achieve our goals. When we associate all pain during rehab, all pain during daily activities, all pain during sports activities . . . it’s when we associate all pain we experience with damage that we limit our function and abilities. So for those in rehab now, demand your physical therapist address this issue and make sure the pain you are experiencing is good pain and works toward your goals.