“My doctor tells me that running causes arthritis, is that true?”

“My doctor tells me that running causes arthritis, is that true?”

I can’t tell you the number of times I have been asked that question in one form or another. The question (and underlying assumption) makes sense. Consistent pounding over a number of years should cause some type of damage. Before answering that question, let’s take a look at what arthritis is and why running might cause it.

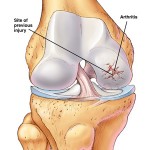

At each “regular” joint (like the knee, hip and shoulder), there is a lining of cartilage where the bones meet. As an example, the hip is a ball and socket joint that involves the pelvis (the three pelvic bones form the socket) and the femur (the upper part of thigh bone is the ball). Cartilage covers the surfaces of both the ball and the socket. This cartilage helps to protect and smooth the movement that joint allows. (Keep this information filed away for a minute, we’ll come back to it soon.)

There are several variations of arthritis, but the type most people think of, and the type we will be referring to, is osteoarthritis.  Arthritis is from the Latin meaning joint (arthro) inflammation (itis). Osteoarthritis (referred to as simply arthritis, for the remainder of this article) is not technically an active inflammation like some of the other arthritic conditions; rather, osteoarthritis refers to a breakdown of the cartilage that lines the joint surfaces (as described above). In very general terms, this breakdown occurs when the joint cartilage mentioned previously undergoes excessive mechanical stress.

Arthritis is from the Latin meaning joint (arthro) inflammation (itis). Osteoarthritis (referred to as simply arthritis, for the remainder of this article) is not technically an active inflammation like some of the other arthritic conditions; rather, osteoarthritis refers to a breakdown of the cartilage that lines the joint surfaces (as described above). In very general terms, this breakdown occurs when the joint cartilage mentioned previously undergoes excessive mechanical stress.

So what causes arthritis?

A 2010 article published in the Journal of Human Genetics concludes that “(o)steoarthritis is a polygenic disease with a definite genetic component . . .” There has been a lot of research into the genetic component of arthritis with nearly all articles agreeing that the genetic component of arthritis is very real. (Click here for more info on genetics.)

As previously mentioned, arthritis occurs when joint cartilage undergoes excessive mechanical stress. So if this is so, why don’t younger people tend to get arthritis? The answer lies in the ability of the body’s cells, tissues and other structures to keep things stable. As people age, the body is less and less able to preserve the body’s normal environment. (Click here for more info on age.)

We can’t really do much about age or family history, but there are things we can control.

Obesity—having an excessive amount of body fat, as often measured by the body mass index (BMI)—has reached epidemic status according to many. There are so many deleterious effects of being obese that books have been written about them. Instead of delving into all the negatives obesity carries with it, important to this discussion is its impact on joint health. Obesity is really where we should be concentrating much of our preventive efforts; aside from reducing the risk of joint degeneration, so many other positives will occur . . . but I digress.

It has been suggested that for each additional kilogram of body mass a person has, an astounding four kilograms of additional compressive force is transmitted through the knee! Recently published research concludes that, “high BMI increases the risk of knee osteoarthritis and severe osteoarthritis.” Further, bariatric (basically weight loss) surgery and a simple exercise and diet program that promotes weight loss both improve function in those diagnosed with arthritis.

In addition to obesity, previous injury to the knee is one of the biggest contributors to arthritis. The incidence of knee  arthritis following ACL or meniscal injury increases significantly. As an example, when a person tears his/her meniscus, more often than not, the only surgical option available is to remove the torn portion of that meniscus. That removal focuses the stress on the articular cartilage and bone because that meniscus is no longer there to perform its role in the knee. In addition, older age at the time of trauma appears to predict a more rapid deterioration to OA of the involved knee.

arthritis following ACL or meniscal injury increases significantly. As an example, when a person tears his/her meniscus, more often than not, the only surgical option available is to remove the torn portion of that meniscus. That removal focuses the stress on the articular cartilage and bone because that meniscus is no longer there to perform its role in the knee. In addition, older age at the time of trauma appears to predict a more rapid deterioration to OA of the involved knee.

Arthritis appears to be more common in those who perform heavy physical work and particularly in those whose jobs involve knee-bending, kneeling or squatting. For example, among those with significant repetitive squatting or kneeling at work (e.g., carpenters, miners), knee arthritis is much more common than in the general population. Interestingly, a study in the 1990’s suggests that nearly 20% of all knee arthritis may result from occupations involving repetitive knee use.

So think back to that sentence earlier, “arthritis occurs when the cartilage undergoes excessive stress.” So obviously running is excessively stressful and breaks down the cartilage, right? Well . . .

Running does increase the force inside the body. When running, the body absorbs up to eight times his or her body weight during each running step.

So, the big question, does running cause arthritis?

Several older studies appear to suggest that yes, running does cause arthritis. But when looking closer at their findings, the conclusions are suspect. One article implicates running as a cause of arthritis, but they actually state that its impact is essentially the same as increased age.

More recent articles (the above cited article involved data from the 1970’s . . . before many of you were born!) have some different thoughts, however.

One of the most recent studies related to this was conducted by Stanford researchers and published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine in 2008. In this study, the Stanford group followed 45 long distance runners and 53 non-runners over a period of 18 years. They evaluated arthritis by studying the x-rays of the participants and grading them based on joint space width and providing them with a Total Knee Score (TKS). The Stanford group found that while runners had significantly worse overall knee scores at the beginning of the study , they actually had better knee scores at the end of the study! In other words, non-runners appear to have experienced a more rapid progression of knee damage. Further, more non-runners had arthritis and knee replacement surgery by the end of the study.

The Stanford group also published a study looking at more indirect measurements of running’s effect on lifestyle. In this study—also published in 2008, this time in the Archives of Internal Medicine—nearly 1000 subjects (538 runners, 423 healthy non-runners) completed a health-related survey before and following a 21 year period. Fifteen percent of the runners died during that 21 year time frame, but 34% of the non-runners passed away. Stated differently, this study found that non-runners were 39% MORE likely to die than runners! While that is not a direct reflection on arthritis, Dr. Chakvarty’s group also found that runners were significantly LESS likely to be physically disabled than their (previously) healthy non-runner counterparts.

Lastly, running has too many benefits to ignore. Research has shown that runners:

√Are better able to maintain proper body mass/weight

√Maintain overall mobility and function more effectively

√Better preserve their range of motion

√Perhaps most interestingly, runners appear to have thicker articular cartilage than their non-running counterparts. Researchers have suggested that this thicker cartilage actually serves a protective role . . . stated differently, runners might actually have a decreased risk of arthritis (this has yet to be definitively shown, but it is possible)!

So, some runners do get arthritis—runners with a history of lower body injuries, overweight runners, runners with poor mechanics—but running in and of itself does NOT appear to cause arthritis.